New Edith Cowan University (ECU) research suggests that acute stress may impair key brain functions involved in managing emotions—particularly in people living with 'distress disorders' such as depression, anxiety, and borderline personality disorder.

The study by ECU Masters student Tee-Jay Scott and Professor Joanne Dickson found that rather than enhancing mental focus in high-pressure moments, stress may temporarily disrupt executive functions—the brain's control processes that help with problem-solving, planning, and emotion regulation.

"These executive functions are vital for controlling emotional responses, especially in challenging situations," Mr Scott said.

"Our findings suggest that people with distress-related disorders may be more vulnerable to having these executive functions disrupted under stress, even when their symptoms don't meet the threshold for a formal diagnosis."

Stress weakens emotional control tools

Executive functions, such as working memory (holding and using information), response inhibition (resisting impulsive actions), and cognitive flexibility (adapting to change) are key to maintaining emotional balance.

The ECU research reviewed 17 international studies examining how these mental skills are affected by acute stress in people with symptoms of depression, anxiety, or borderline personality disorder.

"We found that working memory is particularly vulnerable to stress in people with depression, and that response inhibition—essential for self-control—may be impaired in those with borderline personality disorder," Mr Scott explained.

Implications for therapy and treatment

Professor Dickson said these disruptions could help explain why some people don't respond well to common treatments such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), which relies heavily on these executive functions.

"Many psychological therapies are cognitively demanding," she said.

"If acute stress is interfering with the mental processes that support emotion regulation, it could undermine a person's ability to benefit from these treatments—especially during periods of heightened distress."

A call for new approaches

The researchers say the findings highlight a need for more tailored interventions that account for stress-related cognitive disruptions.

"This research opens up new avenues for understanding how and why distress symptoms and disorders develop and persist," Professor Dickson said.

"It also points to the importance of designing therapies that are more flexible or that build executive function capacity before emotionally challenging work begins."

Next steps

While the study confirms a pattern of executive function impairment under acute stress, the researchers say more research to understand individual differences and refine treatment strategies is needed.

"Understanding how stress interacts with brain function is key to improving mental health outcomes," Mr Scott said.

"It's not just about what therapy is used, but when and how it's delivered that will help ensure its effective."

The paper 'Effects of acute stress on executive functions in depression, generalised anxiety and borderline personality disorder' is published in the Journal of Affective Disorders Reports.

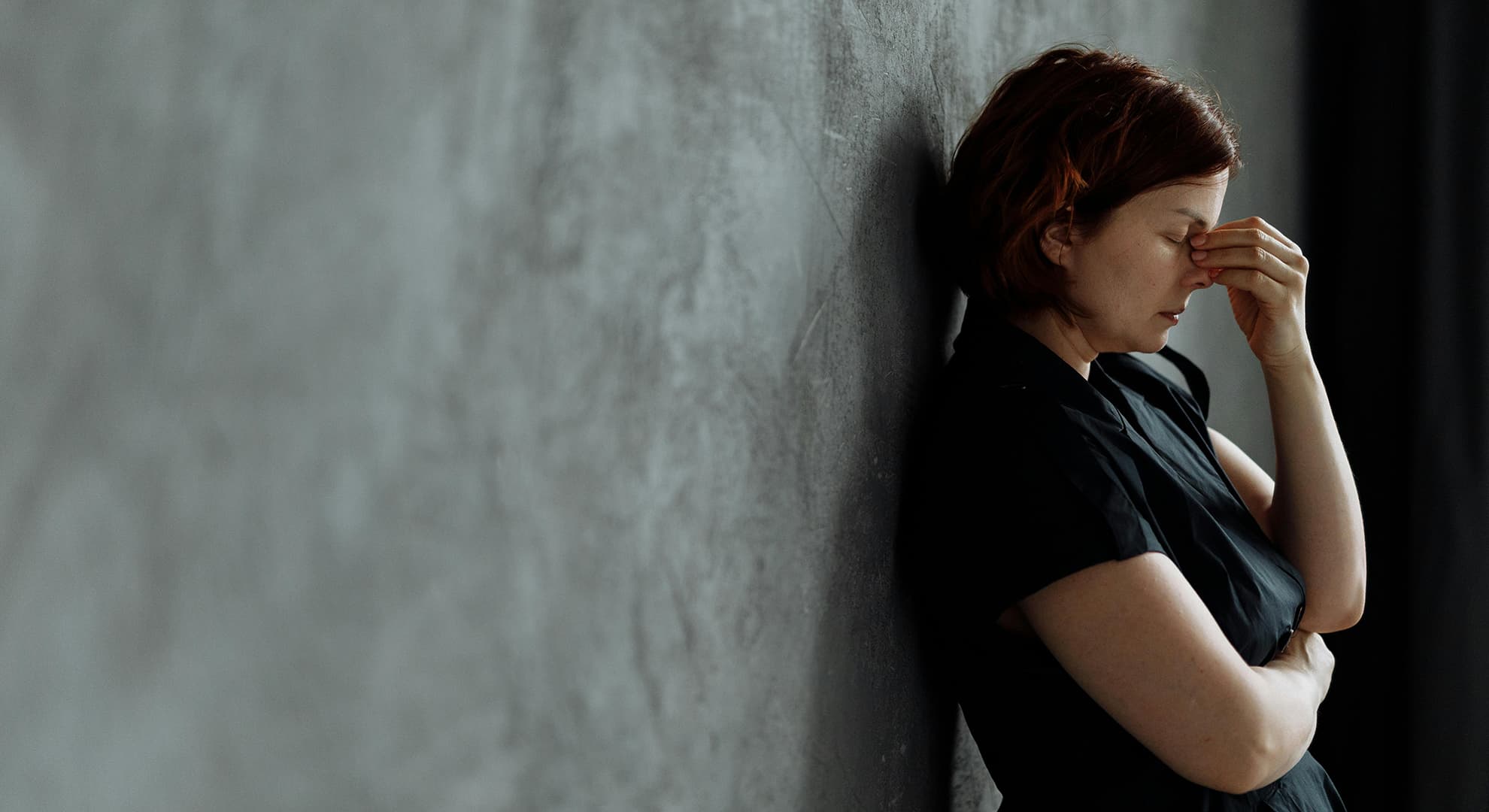

New Edith Cowan University (ECU) research suggests that acute stress may impair key brain functions involved in managing emotions - particularly in people living with 'distress disorders' such as depression, anxiety, and borderline personality disorder. Image credit: Pexels.

New Edith Cowan University (ECU) research suggests that acute stress may impair key brain functions involved in managing emotions - particularly in people living with 'distress disorders' such as depression, anxiety, and borderline personality disorder. Image credit: Pexels.